The subject of refugees is never very far from the political spotlight. In recent years, various fringe groups and minor political parties have expressed strong anti-refugee attitudes. And - in the past eighteen months or so - these views have even been echoed by some mainstream politicians.

Amidst all the shouting it is easy to overlook the fact that the vast majority of refugee immigrants end up as hard-working New Zealand taxpayers. In fact, many of them do more than that - and go on to play crucial roles in commerce, the arts, and in scientific research.

It is unfortunate that our politicians never shout about these ordinary refugee success stories. But to help counteract their silence on the subject, two of my friends - both of whom arrived in New Zealand as refugees - kindly allowed me to interview them for Public Address. In the first part of this post I talked to Shahzad Ghahreman, the highly-respected Liaison Librarian and Archivist at the Auckland University of Technology. This second interview is with Lan Le-Ngoc, one of the key scientists at Industrial Research Limited in Christchurch.

Lan had just turned fourteen when he arrived in this country - the only other surviving members of his immediate family were left back in Vietnam. He discusses his experiences as a child during the Vietnam War, and his early life under the communist regime.

Lan grew up in New Zealand to become both an engineer and scientist. His research is currently focussed on two important areas: ocean wave energy systems for electricity generation, and assistive devices to help increase the independence of the physically disabled. He has numerous scientific publications to his credit, as well as a number of commercial patents which have added significant value to New Zealand industry. His scientific work was recognized by a Royal Society Medal in 2001.

Lan was delightful to interview. He is witty, entertaining, and one of the nicest blokes you could possibly meet.

* * *

My name is Lan Le-Ngoc. I was born in Saigon (which is now known as Ho Chi Minh City) in 1964. At that time my father was serving in the South Vietnamese army, and my mother was employed by the Reserve Bank of Vietnam. I am the youngest in the family; my sister is nearly two years older than me.

One of my earliest recollections is the shelling of Saigon during the Tet offensive in January 1968. I would have been four years old at the time. It sticks in my memory because the emergency sirens woke me in the middle of the night. I knew that I had to run to the bomb shelter, but in my haste I managed to get myself stuck in the mosquito net that hung over my bed. I was still half-asleep, and began to panic - but my struggles to get free only made me more tangled in the net. I could hear my mother's anxious voice in the bomb shelter asking where I was, and then the whole family started to shout out my name. My mother rushed back into the main part of the house, and I can still recall the enormous sense of relief when she disentangled me, and then carried me out to the safety of the shelter.

Despite events like this, my early childhood seems very ordinary to me. The war was just another aspect of day-to-day life - mostly it was in the background. In a lot of ways we were quite similar to a New Zealand family of the same period. My parents owned a car, and had just purchased a small house. They had a savings account at the bank, and insurance policies - all the usual things. I went to kindergarten, and my sister went to school. Our lives were very conventional.

Everything changed when I was six. My mother died of cancer, and my sister and I were sent to live with our grandparents in another part of Saigon. My father couldn't come with us - army regulations meant that he had to live close to the military base. That was very difficult. We didn't like being separated from our father, but he was very conscientious about visiting. He would cycle across town every evening to spend a few hours with us before we went to bed.

After the signing of the Paris Peace Accords in 1973, everything began to look more hopeful. People became quite optimistic about the future. The fighting had stopped, and my father even took us on holiday. We went into central Vietnam, which had previously been far too dangerous to visit. It was the first time I had travelled north of Saigon, so I was very excited.

But then the war started up again. At the beginning of 1975 I was sitting an exam, and suddenly a fighter-bomber flew right over our school. It dropped a bomb which exploded just across the road. We had to evacuate the classroom, and go to a safe area outside the school. As a ten-year-old I didn't really feel frightened - in fact, I was rather pleased to get out of the exam. Shortly afterwards the schools were closed indefinitely, and there were no more exams at all. So I was at home when the government surrendered on April 30th, and the North Vietnamese tanks rolled into Saigon.

My grandparents' house was close to a prison, and the first thing the North Vietnamese did was to unlock all the cells. Some of the inmates were political prisoners, but a lot of them were real criminals. They came pouring out of the prison, and managed to get hold of some automatic weapons. All afternoon there was continuous gunfire on the street where we lived. We were terrified - and locked ourselves in the bomb shelter where we would be safe from the bullets.

My father was in the military compound while all this was happening. Everyone was being evacuated to the US bases in Guam. The army wanted him to leave as well, but he protested, saying: "If I go then who will look after my children?". So he was allowed to remain behind. He put on his civilian clothes, and tried to make his way to my grandparents' house. By this time the military compound was under heavy fire, and several times he was nearly hit by artillery shells. When he got outside there were North Vietnamese soldiers everywhere, and dead bodies of South Vietnamese people lying in the street.

He arrived home that evening, and my sister and I were extremely relieved to discover that he was safe. The whole family were together in the house that night. But after we children had gone to bed some North Vietnamese soldiers came to the front door. They started waving their guns around, and shouting out for my father. Everything became terribly chaotic - people were screaming, and my sister and I hid inside the bedroom with my uncle. But my father was amazingly composed. He calmly greeted the soldiers, and answered their questions in a very self-assured manner.

It turned out that one of my father's subordinates had betrayed him to the North Vietnamese. The subordinate was actually there in the house - giving the soldiers information about my father. They were trying to discover the whereabouts of some of my relatives who had been serving in the armed forces. The subordinate was telling the soldiers about my father, and saying: "He's got a son and daughter - they must be somewhere in the house as well."

At that point my uncle grabbed my sister and me, and took us out into the back garden. His motorcycle was nearby, and he put us both on the pillion and drove to his house. It wasn't a pleasant journey. The streetlights weren't working, and the night was absolutely pitch black. From time to time we could hear gunfire from the surrounding streets. The whole city was under military curfew - we would have been in serious trouble if we'd been caught.

The next day we discovered that the North Vietnamese soldiers had arrested my father. It was a very worrying time - we didn't hear any news for about a week. But then one day my father arrived back at my grandparents' house. It turned out that the North Vietnamese regime didn't really know what to do after the fall of Saigon. So they just took people like my father into custody. He hadn't been treated badly - they'd only asked him a few simple questions and then let him go.

By that time the city had calmed down a bit, and everyone had begun to get used to the new situation. After a few weeks the new regime announced a plan. All the people from the South Vietnamese army and government would have to go through a re-education programme. They would be taught about the communist system, and how to be a good citizen in the new Vietnam.

We were advised that the programme would take one month. A lot of my family members were ordered to go: my father, some my uncles and aunts, and various other relatives. Because my father had already been in North Vietnamese custody we weren't really too concerned about the situation. They'd already let him go once - it seemed logical that they'd let him go again. If they'd had any unpleasant ideas, they would have carried them out the first time they had the opportunity.

So we didn't suspect a thing. I can remember helping my father to pack some clothing and other items into a small bag. He seemed quite unconcerned when he said goodbye to us all. We waved to him as he left the house, and he called out cheerfully: "See you in a month!".

Of course, my father and all of my other relatives just disappeared. We didn't hear anything about them again. A month went by, and then six months, and then a year. Even after three years the only thing we knew was that they were still undergoing re-education.

In the meantime, Vietnam had become a desperate place. It was like industrialization in reverse. In the early 1970s we'd had lots of cars in Saigon. Then, towards the end of the war, petrol became very expensive and everyone rode around on motor scooters. After the communists took over there were only bicycles left. Factories closed down, and all sorts of essential services fell into disarray. Everything was rationed. Food was very strictly controlled, and people were only allowed to buy a small amount every week.

With so many family members in re-education I honestly don't know how we survived. But somehow my grandmother managed to cope. I was in charge of getting her around the city. She would sit on the back of my bike, and I would pedal her wherever she wanted to go: shopping, visiting the temple, and so on. I became very good at navigating around the different parts of Saigon.

School eventually reopened. It was rather different from before: we learnt all about Ho Chi Minh, and the communist version of history. The fact that my father was in re-education meant that I had no opportunity for any sort of higher learning. Those with relatives in re-education weren't allowed to pass the advanced exams.

I had no prospects outside school either. A father in re-education would have disqualified me from any sort of career. I would only have been permitted to do the most unskilled sort of work, or could perhaps have been a low-ranking soldier in the army. The latter became a very real possibility when Vietnam declared war on Cambodia in 1978. Teenage boys were being conscripted into military service. My fifteen-year-old cousin - only a few years older than me at the time - was sent off to fight the Khmer Rouge. I'd always expected to go into the army, so I didn't mind the idea of being a soldier, but not on the side of the North Vietnamese.

By this time, life in Vietnam had become so bad that lots of people were trying to leave. My uncle was trained as a navigator, and he was approached by a group of Chinese-Vietnamese who wanted to escape. They had purchased an old boat and bribed some local officials to let them sail into the South China Sea. They offered my uncle a deal: in exchange for navigating their boat he would be allowed to bring along his wife and children. They would be able to start a new life elsewhere.

My uncle also managed to negotiate a passage for his youngest sister (my aunt), who was only a few years older than me. I remember that I took my grandmother down to the river to see them off. It was quite an event. The local officials were there with a couple of policemen to make sure that no-one got aboard the boat without paying them a bribe. Some of my other relatives were there as well. One of them took me aside, and told me that I should try to sneak onto the boat.

I thought this was a crazy idea. The local officials were running a very strict boarding process. They would call out each name from their list, and carefully check the person's identification papers. Two policemen would let the person onto the jetty, and would supervise them as they climbed into a water-taxi. The water-taxi would transport about thirty people at a time to the main boat. It would have been quite impossible to sneak aboard without anyone noticing.

I could sense that my relative was serious about trying to get me onto the boat, and so - to avoid an embarrassing situation - I hid myself behind one of the sheds on the waterfront. Later on I heard my aunt's name being called out. So I came out to wave her goodbye, and as I did so, my relative caught sight of me. He grabbed me and asked angrily: "Why are you still here? Get yourself on that boat!".

I became really annoyed with him; he was making an impossible request. So I started marching down the jetty - deliberately trying to be caught by the policemen. I think it crossed my mind that when they arrested me I'd point out my relative and say: "He made me do it!". But by pure chance, when I got there, the policemen just happened to finish with the last person on the list. So they turned around and walked down the jetty. The next thing I knew I had walked behind them all the way to the water-taxi.

The policemen got into the water-taxi to count the number of people aboard. They didn't want any possibility of a stowaway. I stood behind them at the edge of the jetty, and thought to myself: "Do I step down into the water-taxi with them, or do I stay here?" I put my foot out - but I was still undecided. And then I slightly lost my balance, and had to step down into the boat to regain my footing.

That one step completely changed my life. There was enough room behind the policemen for me to sit down. When they finished counting they didn't give me a second look - even though they had to step over me to get out of the boat. I suppose they must have thought they'd already counted me.

The water-taxi went a surprisingly long way down the river before it arrived beside the boat. I looked up and saw my uncle standing on the deck - which was very reassuring. Then I noticed that several policemen were on the deck with him. They were double-checking the list to see that no-one got aboard who hadn't paid the bribe money.

The water-taxi pulled up beside the boat, and - as luck would have it - I was the closest person to a policeman. He reached down to help me aboard. I had no idea what to do. So in sheer desperation I took the baby from the woman beside me, and handed him up to the policeman. Then I started lifting out everyone's bags, and helping all the other passengers to disembark. People were saying "Thank you very much, young man" and making approving comments about my politeness.

Eventually there was a long queue of people on deck, and then I climbed aboard. One of my uncle's friends had been watching me. He grabbed me and smuggled me into the group of people who had already been counted. There was absolutely no planning in my escape from Vietnam - everything happened by complete accident.

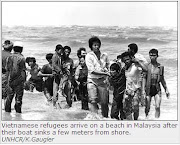

Finally the policemen and local officials left the boat, and we set off down the river. The trouble began when we reached the sea. There were over 250 people aboard a 21 metre boat - it was terribly overloaded. As soon as we hit the waves it tipped over onto one side.

My uncle took charge of the situation, and told everyone that we were going back to Saigon. He said that the boat was too dangerous to take to sea, and that we'd all end up drowning. But the refugees started shouting and arguing with him. They'd sold everything - their houses and all their belongings - to pay the bribes so that they could leave. They said they weren't going back.

The situation got quite nasty, and in the end my uncle was forced to continue the voyage. But he managed to get a compromise from the refugee leaders. He persuaded them to bring all the luggage up from the cargo hold and throw it overboard. Then he loaded everyone down under the deck, so as to lower the centre of gravity of the boat.

The refugees were packed in like sardines; there wasn't an inch of space anywhere. The cargo hold had no lighting - everyone was in complete darkness. I could hear people groaning and retching, and even from the deck we could smell their vomit. But my uncle's plan made the boat much more stable, and enabled us to get moving again.

I wasn't a member of any group, so I was probably the luckiest person on the whole boat. No-one ordered me into the hold with the other refugees. Instead I made myself useful helping the crew on deck - carrying things for them, and so on. I didn't feel seasick at all.

Towards the end of the day the crew finished their work. I stood at the railing and looked back at Vietnam. I tried to memorize every detail - thinking that one day I'd return. It was strange because although I'd been there all my life I'd never before seen it from the outside. In my mind, Vietnam meant the city of Saigon. But from the sea it looked just like in the movies. I could see banana plantations, and rows of coconut palms; the jungle looked very green against the water. I stood there just watching my country, as night fell, and it slowly disappeared into the darkness. I was thirteen years old.

That night a storm came and I got very seasick indeed. The boat was listing steeply over onto its side. Every so often a big wave would hit us, and it would flip over onto the other side. It felt like we were going to sink at any moment. The rough weather was with us for several days, and I was seasick the whole time. I became very dehydrated. I remember that at one stage I managed to glue my face to the floor of the wheelhouse with my own vomit. It must have been absolutely terrible for the refugees in the cargo hold.

On the evening of the fourth day we reached Malaysia, and my uncle managed to navigate the boat into the harbour at Kuala Terengganu. The water was calmer inside the harbour, and everyone began to recover from their seasickness. We moored our decrepit boat beside a group of expensive-looking yachts. We could see the glow of the city lights, and the head-lamps of cars driving on the road beside the bay. Civilization again! It was very exciting.

Morning arrived, and the citizens of Kuala Terengganu awoke to find us moored in their harbour. Nobody came out to see us, and we didn't know what we should do. So a couple of people from our boat jumped into the water, and swam to the land. As soon as they arrived they were beaten up by the Malaysian police. Eventually the police dumped them back in our boat, and then towed us out of the harbour into the river.

We were moored on the river until evening. The people in the hold were getting very edgy. I think someone tried to make a hole in the hull so that they could escape. The boat began to get very unstable as everyone moved around. I could hear a lot of voices shouting below deck. Then the police returned with a flotilla of small boats. They started to take people aboard, and everyone rushed to try and get off. Our boat began to tip really far over, and for a couple of seconds I thought it would capsize.

The police took my uncle away for interrogation, and I was loaded onto one of the small boats with some other refugees. We were taken to Paulo Bidong - a deserted island which the Malaysian government had decided to use as a refugee camp. They offloaded us onto the coral reef, and then we all had to wade through a lagoon to reach land.

Once ashore, everyone just stood around looking exhausted and confused. Then some of the refugees who were already on the island came down to the beach, and recognized their relatives in our group. Everyone started talking excitedly in Chinese, and in the midst of all this the police arrived with guns. They made us get into an orderly queue, and then took down our names for their immigration records.

By the time the police were finished, all the Chinese-Vietnamese refugees had been found by their relatives. Just my uncle's wife, her children, and my young aunt were left with me on the beach. None of us had any idea what to do. We could see one of the Chinese-Vietnamese families disappearing into the distance, and so we decided to follow after them. We tagged along for several kilometres until they arrived at a rough shelter where their relatives were living.

They went inside - which left us in an awkward position. In the end we just lay down outside the shelter and tried to go to sleep. There was nothing else to do. It was the first time I'd slept under the stars.

We had a miserable night. When I awoke the enormity of the situation suddenly dawned on me, and I became very distressed. I missed my sister and grandmother - I wanted to go back home to them.

Matters became even worse when we discovered that there was nothing to eat. The island had no food reserves for new people, and the supply ship wasn't due for another week. We tried to beg food from the other refugees. In the end we found some dried fish that had been thrown away, and tried to make a meal out of that. It had gone bad, and made us all sick.

On that second day we found a sheet of plastics, and collected a few sticks to build a tent. During the night there was heavy rain, and it turned out that we had constructed our new home in a river bed. The water rose up inside the tent, but we were so starved and exhausted by this stage that none of us could get up. We just lay there and let the water wash over us. I actually slept half-submerged in the river.

The next morning someone took pity on us, and give us a little rice to eat. Those first few days on the island were really hard - probably the worst experience in my time as a refugee. But my uncle arrived back on the next supply ship, and soon had us all sorted out. Eventually he managed to obtain some corrugated steel sheets, and built a two-storey shack. Apart from the cladding, the whole structure was created from tree branches - even our beds were made of branches. Under those circumstances it was like living in a mansion.

I soon fell into a routine on the island. In the morning I would collect water from the wells, gather firewood from the forest, and then queue for our food rations. In the afternoon I was free to do whatever I wanted. I made friends with some other kids my own age, and we used to swim at the beach and explore the coast. Later on my uncle found someone who spoke English - so we also had language lessons to keep us occupied.

But all of this was simply marking time. Everyone had applied to be settled in new countries, and we were all waiting for our cases to be considered. I had a relative who had been to university in New Zealand, and when Saigon had fallen he had been able to go back there. So I put New Zealand down as my first choice - but I also applied for Australia and the USA.

I had to wait about five months to hear from the New Zealand authorities, and in the meantime my other refugee applications were rejected - which was quite worrying. Australia had accepted my uncle's application, so it seemed like our group would be split up. He and his wife and children would be flown to Sydney, and my young aunt and I would be left behind on the island.

It turned out, however, that New Zealand had been working behind the scenes. One morning some officials turned up and interviewed me and my aunt. The next week New Zealand arranged for the Malaysians to send us to a transfer camp in Kuala Lumpur. So we actually ended up leaving the island before my uncle.

In the transfer camp we met up with about a hundred Vietnamese all going to New Zealand. We were flown to Singapore, and then a delegation of New Zealanders met us at the airport. Life completely changed as soon as the New Zealanders took us under their care. We were taken straight to the New Zealand army camp and given a proper meal - which seemed like an absolute banquet in comparison to our refugee camp diets.

This was actually the first time I spoke English in a real situation. A New Zealand soldier came up to me and asked: "How old are you?" He spoke so quickly that all I heard was 'how' and 'you'. So I took a guess and replied: "Fine thank you." He looked a bit surprised at that, but then he figured out that he needed to slow down - and we managed to have a simple conversation in English.

After our meal we were put on a plane to Auckland. The main thing I remember about the flight was the pleasure of being cool after the constant heat and stickiness of Malaysia. When we arrived in Auckland airport I was astonished by the temperature of the terminal, and thought: "Wow, this whole building is air-conditioned - it's even colder than on the plane". Then I went outside, and it was even colder still. For a few seconds I had the crazy notion that New Zealand had air-conditioning outdoors - it was so strange for me to be outside and cool at the same time.

We were taken directly to Mangere hostel, and given our own rooms with beds and pillows and sheets and blankets. It seemed incredibly luxurious in comparison to what we'd experienced over the previous six months. We were at the hostel for about three weeks, I think. In the mornings we had English classes, and in the afternoons we learnt about New Zealand culture. We were even given spending money, and encouraged to go to the shops to buy small items for ourselves.

There was a very nice Maori family staying in a different part of the hostel. I used to practice my English on them, and eventually they became my first New Zealand friends. They introduced me to some typical New Zealand foods as well as the game of table-tennis - which I still play today. Those first few weeks in New Zealand were quite formative in terms of my future habits.

At the end of the English course, my young aunt and I were sent to Christchurch to stay with my relatives. I started school almost immediately. Everything was extremely well organized - people were visiting and donating furniture so that we would have all the necessary items. I even got given a bike, which I rode to school on my first day.

I have some very strong memories of those initial months in Christchurch. The first time I had fish and chips on a Friday night: learning how to tear the top off the newspaper to get the chips out; hugging onto the hot packet to keep myself warm. Or the first time it snowed: sitting in a classroom, and suddenly realizing that snowflakes were drifting down from the sky; watching the students throwing snowballs at lunchtime, and pedalling home through the snowdrifts in the evening. It was just as I had imagined from French stories about winter - it felt like being in a fairytale.

I was surprised to find that I really enjoyed school in New Zealand. My education in Vietnam had been under the French system which involved a great deal of rote learning. I found memorization rather difficult, and wasn't a great student. But I discovered that the New Zealand system emphasized understanding rather than rote learning - an approach that suited me much better.

I was put straight into a third form class, which I found pretty hard until my English improved. But the teachers were really good, and gave me lots of extra help. As soon as I overcame my language difficulties everything got much easier. By fifth form - much to my amazement - I was top of the school in maths, science, and technical drawing.

After sixth form I decided to leave school and go to work. My family in Vietnam had managed to contact my father in a North Vietnam prison, and so I wanted to earn money to send to him and my sister. I was also keen to move out on my own - and allow my relatives some time to themselves.

But the teachers at school were very unwilling to let me leave, and when I explained my reasons they said: "We'll try to find you money somewhere - we really think it's important for you to finish school and go to university". So they arranged for me to have a meeting with the principal, and he managed to find me scholarships at the Rotary Club and Riccarton Trust.

The scholarships provided enough money for my needs during seventh form, and I was able to supplement the income with a part-time job. I was also offered the chance to board with one of my friend's families, which resolved my only other obstacle to staying on at school.

I was really determined to make the most of my opportunities during that seventh form year. I worked hard at school during the day, and studied every night. In the weekends I'd get up very early and cycle to Meadow Mushrooms in Prebbleton. I'd put in a full day's work at the mushroom factory - and then hit the books again when I got home. It was a hard year, but very enjoyable because I had such a clear goal to work towards.

At the end of the year I passed my exams, and also managed to win a university scholarship. With my bursary and living allowance I would be getting almost as much as a real job. I felt incredibly privileged - being paid to study seemed almost too good to be true.

The only drawback to the scholarship was that I was expected to go directly into second year at university. I had decided to do mechanical engineering, which is a really tough course at the best of times. Skipping first year meant that I had a lot of catching up to do. But I studied really hard, and at the end of the year I was awarded another scholarship for being the top student in mechanical engineering - much to my surprise.

A consolation for the stressful workload was my home life. In my first year at university I boarded with a retired couple, and I lived like royalty. Real kiwi food: lots of meat and vegetables followed by a nice pudding every night. And then a big roast dinner on Sunday with wine and all the trimmings. It was pretty wonderful.

During summer I did my practical work experience as an engineer. The next year I moved into a big flat in Ilam with some of my university friends. We had a very multi-cultural household, and I ended up living with Nigerians, Samoans, Tongans, Fijians, Malaysians, Sri Lankans, Solomon Islanders, and Cook Islanders as well as lots of New Zealanders.

I met so many nice people at that flat over the years - they really made me part of their family, and used to include me in all their social activities. I was actually a paid-up member of the Samoan club, the Fijian club, and the Tongan club all at the same time. In retrospect it must have looked quite funny when we were out together. A group of big strong Pacific islanders, and this skinny Vietnamese guy.

I finished my mechanical engineering degree with first class honours, which meant I could go straight on to a Ph.D. But doing more study was the last thing on my mind. I'd just heard that my father had been released after more than a decade in a prison camp, and I was desperate to bring him and my sister to New Zealand. There were a lot of obstacles to this plan. I knew that I'd need a decent income to afford the immigration costs.

But again, fate conspired to keep me at university. I was awarded a doctoral scholarship, which meant that I would be paid a generous stipend to study for a Ph.D. And when I mentioned that I had no intention of accepting the scholarship, I got a long lecture from my professor about missing the opportunity of a lifetime. So in the end - slightly against my will - I found myself enrolled in the Ph.D. programme. Again, like so many other events in my life, as a consequence of accidental circumstances.

It turned out that I wasn't so busy during my Ph.D., and so I decided to offer some of my time to coach school-children who were having difficulties with maths and science. I ended up with four kids to tutor every Saturday morning. It was quite hard work, but it ended up being very worthwhile because one of my students had an older sister who was really nice. Exceptionally nice, actually. And one day I plucked up enough courage to ask her out on a date. Six months later we were engaged.

That put the pressure on me to finish my Ph.D. as quickly as possible - I didn't want to get married while I was still a student. And, of course, I wanted to have my father and sister at the wedding. This was a problem because my application to bring them to New Zealand had been turned down by the immigration service.

That was a very difficult and upsetting situation. I tried every possible avenue to get my case reconsidered: I applied for a special hearing on compassionate grounds, my friends wrote letters supporting my submission, I even got the local member of parliament to talk to the immigration service on my behalf. But nothing worked - it was really devastating.

And then one day - completely out of the blue - I read in the newspaper that the immigration service had changed its rules. And under the new criteria I was eligible to re-apply. And when I resubmitted my application everything went smoothly, and my father and sister were accepted into the country.

The year 1990 was a real annus mirabilis for me. At the beginning of the year I handed in my Ph.D. Then my father and sister came to New Zealand, and we were finally re-united as a family. Then I got my job as a scientist at the Department of Scientific and Industrial Research (DSIR), which enabled me to buy a nice house for us all to live in. And then, at the very end of the year - on Boxing Day - I got married.

Since then we've had two children. Our family has a very conventional life-style: typical New Zealand food, and the same sort of day-to-day activities as everyone else. My son and daughter are both very passionate New Zealanders - in fact, my son wears red and black rubber-bands on his braces to support the Canterbury Super-14 team. My daughter is a keen netball player, and studies art, dance, and music in her spare time. I occasionally think it would be nice if they were more in touch with their Vietnamese heritage, but as long as they're happy I don't really mind.

Over the years I've had a lot of pressure to leave New Zealand from my extended family in Australia and the USA. I know that I could earn much more money in these countries - but I'm not a person who is particularly motivated by that sort of thing. It's more important for me to make a contribution to New Zealand, which I hope that I do through my science work. My passion is to help solve the problems that face all of humanity, and to improve everyone's quality of life.

The only trouble - and this is very hard for me to say - is that these days I'm not entirely sure if New Zealand wants me. I feel that I'm appreciated in my profession and within the science community, but on the streets I get a very different reception. People who don't know me will often treat me quite rudely. In fact, sometimes they are actually insulting.

This behaviour is a comparatively new phenomenon - just in the last five years or so. I never saw it when I was a teenager, and I certainly didn't live in a posh area or attend any sort of exclusive school. I had summer jobs picking fruit in the orchards down in Clyde, and worked with all sorts of New Zealanders; and I don't recall any incidents of racism at all. But recently it seems to be everywhere. I've had people shouting abuse at me from cars. Even children - that's the worst.

Only a few weeks ago I dropped my daughter off at school, and as I went back to my car there were some kids standing at the front gate. Just primary school children - only nine or ten years old. And one of them shouted at me: "You f**king Asian. Go home!"

That incident really depressed me - because you can judge a society by its children. Where would a child have learnt those attitudes? Just nine or ten years old, and already he thought that Asians shouldn't be in this country. The message is actually out there in society for him. It was a terribly worrying thing to happen at my daughter's school, and it's a real concern of mine that these new racist attitudes might affect her as well.

I suspect that part of the responsibility for such attitudes can be laid at the feet of certain politicians. The rhetoric of people like Winston Peters and Don Brash has actually promoted anti-immigrant sentiment. It was probably always there to a certain extent, but when senior politicians start spouting this sort of nonsense then it isn't merely airing the views of a racist minority - it actually starts to incite racism.

Easily-led people take such political rhetoric as legitimization of their own bigoted views. They think it gives them carte blanche to treat immigrants rudely in shops, or to shout insults from their cars. Of course, I'm not suggesting that this is the intention of Peters or Brash. They're just doing it to get votes. I'm sure that after the election they forget all about it. But they don't realize the long-term impact that it's having on people like me and my family - who can be easily identified as having ancestry from somewhere other than Europe.

The ridiculous thing about being told to "go home" is that I've lived in New Zealand twice as long as I lived in Vietnam - I've been here for nearly half my childhood and all my adult life.

I am home.

source :

http://www.publicaddress.net/default,3529.sm#post