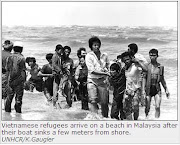

A disaster points up the plight of Viet Nam's seaborne escapees

The frail fishing boat, packed with some 250 men, women and children fleeing Viet Nam, arrived off the east coast of Malaysia early last week. When it tried to dock at Pulau Bidong, an island that holds Malaysia's largest camp of Vietnamese refugees, police prevented the landing. The craft headed for the mainland, but villagers waded into the water and pushed the vessel away from the shore. In desperation, the refugees attempted to negotiate turbulent waters into the mouth of the Trengganu River. Catastrophe struck. The boat hit a sand bar and capsized. A few dozen aboard managed to swim ashore. More than 200 lost their lives.

The deaths dramatized the perils facing a growing flood of seaborne refugees trying to escape from Viet Nam. A few weeks ago, one group was attacked seven times by pirates, who took even food and water before the Vietnamese landed in Thailand. Several other boatloads were so desperate for safety that they forcibly boarded an oil-rig tugboat about 170 miles east of Malaysia. Still another 42 Vietnamese scuttled their craft just off the Malaysian shore, swimming the remaining distance so that authorities could not tow them back out to sea.

Despite the hazards of escape and escape, never since the massive exodus following the fall of Saigon in 1975 has the South China Sea been so strewn with refugees seeking safe harbor. "The flow is so great," reports TIME Correspondent Richard Bernstein, "that countries in the area are becoming increasingly reluctant to accept new arrivals, even temporarily. And as the tide of refugees rises, it is straining the ability—and the willingness —of more distant nations to grant them permanent asylum."

Malaysia is the most striking case in point. So far this month, more than 10,000 people have arrived on its shores. Many of the refugees have heard that acceptance in Malaysia is easier than in other nearby countries. But the number of Vietnamese in Malaysian refugee camps—packed, fetid shanty towns, where food and water are scarce—has surged from a mere 5,000 last spring to more than 40,000 today, and the government has grown progressively anxious about new arrivals.

Even as tragedy struck in the Trengganu estuary, another refugee drama, that of the harborless freighter Hai Hong, was coming to a gradual, troubled end. Jammed with 2,500 refugees, the 1,600-ton Hai Hong arrived off Malaysia near Port Kelang on Nov. 9 after two weeks at sea. The government refused to let the ship dock. It would not allow food, water and medicine to be sent to the freighter until last week, when France, Canada and the U.S. agreed to help resettle all aboard. The Malaysian government still will not permit the refugees stranded on the overcrowded, unsanitary vessel to be quartered ashore. Local officials want the Vietnamese to be transferred directly from the ship to an airport for flights to their new homes. The U.S., which has already admitted 150,000 refugees from Indochina, seeks a different solution. To help the Hai Hong homeless, the U.S. Attorney General approved an increase of 2,500 above the annual refugee quota of 25,000 for the year ending next May 1. But the Carter Administration wants to take the refugees at the head of the queue already in Malaysia, and have the Hai Hong escapees take their places in the camps.

The Hai Hong's passengers—mostly ethnic Chinese—represent a new type of refugee. There is some evidence that the ship and its human cargo left Viet Nam with the knowledge of either the Hanoi government or high Vietnamese officials. Refugees have testified that since July a scarcely concealed escape network has been in existence that allows people, especially of Chinese descent, to leave the country for a price—currently about 10 oz. of gold, or roughly $2,000, per person. "It's all organized by the government," says one Vietnamese Chinese who arrived in Thailand this month. "They want the gold, and they feel that we overseas Chinese are no use to them anyway."

Whether pay-and-escape is in fact Hanoi policy remains unconfirmed. But a number of refugees say that those who want to leave Viet Nam can simply register with a middleman and make a down payment in gold or dollars. They are taken to ports where they hand over the rest of the exit price, then are ferried to a ship just outside Vietnamese territorial waters. At least two such vessels have been used. One is the Hai Hong, the other a 900-ton coaster, the Southern Cross, which ran aground in Indonesian waters last Sept. 21 carrying more than 1,200 passengers.

Malaysia claims that people who leave Viet Nam in such fashion are not refugees but illegal immigrants who should be refused asylum. Others disagree. "These people," says one Western refugee official, "have risked their lives escaping what they consider intolerable conditions. The fact that they paid bribes doesn't make them any less refugees than were Jews who escaped Nazi Germany. Many of those people paid bribes too."

In any case, those who leave Viet Nam via what is called "the big payoff' still constitute a minority. While negotiations over the Hai Hong were under way, well over 4,000 new refugees arrived off Malaysia in smaller groups. Most were granted sanctuary, though by late last week police patrol boats were turning back many small craft.

The numbers demonstrate that many Vietnamese, from soldiers and officials of the old regime to simple fisherfolk, remain deeply dissatisfied with their new masters.

Among the most common complaints are lack of political freedom, food shortages, and the extreme hardships in the "new economic zones," patches of jungle where city dwellers have been forcibly resettled. "Practically everybody talks about escape," says a former Saigon civil servant now in Thailand. "It's just a matter of being willing to take the chance."

It is not only the Vietnamese who show dissatisfaction. Even as the Vietnamese refugees increase, more and more Laotians and Cambodians seek to escape overland. For some time, an average of 3,000 people a month arrived in Thailand; in October, the figure doubled.

Alarmed by the new tide of refugees, U.S. Secretary of State Cyrus Vance last month called on the U.N. General Assembly to convene a conference on the entire question, a meeting now scheduled for Geneva in December. Even before that, the U.S. Congress will hold hearings on the refugees' plight and the possibility of higher U.S. quotas.

source :http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,912259-1,00.html

Wednesday, November 5, 2008

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment